Why we need to talk about History in Medical Education More often

History Still Matters

It's just how we use it.

Medical education offers a snapshot of current practices and literature for many students under the guidance of current practitioners. Educators across all healthcare spheres rely on teaching what the current standards of care and evaluation in the medical environment at present are to help them get them to their clinical experiences prepared. While this offers students the best opportunity to then enter the healthcare space with the most updated knowledge they can have, it also shortchanges them in regards to understanding the process of why we do what we do.

Take for instance the current opioid epidemic. Currently, many schools in healthcare (e.g. Medical, Pharmacy, Nursing) are rapidly expanding classes around opioid-related overdoses and how to develop services for addiction or how to help with acute overdoses (i.e. Naloxone administration). But, the question that is rarely asked by the students is why do we have this problem? What happened in the past two decades of pain-management practices and evidence that allowed this to happen, because it did not develop overnight.

Rarely do I hear educators taking the time to talk about the history of their profession or disease management with their students. There's talk about evidence-based practices, new developments, new procedures, new drugs. We focus on these developments with journal clubs, disease presentations, and grand rounds in the medical education space, but no one takes the time to ask, what did we use to do?

History is a subject that many take for granted in my opinion, where many forget that the past determines the present which shapes the future. In medicine, history demonstrates successes and failures of our currently accepted best practices. As a pharmacy educator, I love the history of drug development for instance, and in every discussion, I have with students, whether in the classroom or small groups, I like to frame our current understanding of what we are doing based on what we used to do.

Example

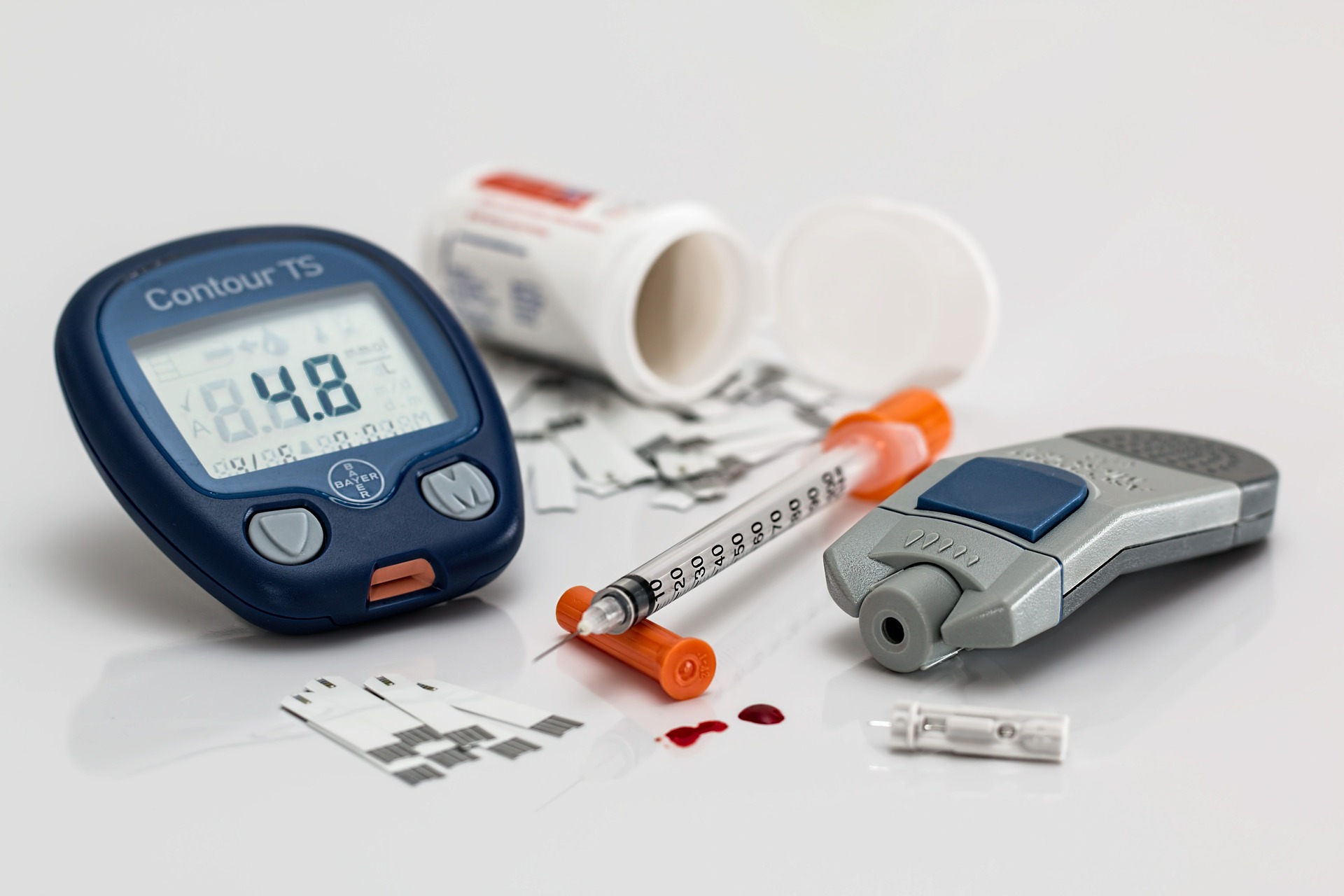

What did we do before insulin?

Take for example Type I Diabetes (sometimes called Juvenile Diabetes). In a recent discussion with students on the management and care for patients with the disease, I asked what did patients do for treatment over a century ago. Many responded that patients took insulin of course. When I asked when Insulin was invented, many could not provide a fast answer, in which case they go on Google, and determine that Banting & Best only made progress on the Discovery of Insulin around 1920. So what happened to those patients before insulin? Well, they died generally. There is a reason that Banting & Best got the Noble Prize in Medicine in 1923 for their research, this was a significant milestone in medicine. And the company that bought their product to launch it into a worldwide pharmaceutical company? Eli-Lilly.

So what do I get out of framing this little tidbit of information with students in discussion? One, it helps frame the seriousness of treatment for Type I Patients and the need for insulin. It's life of death. Second, It helps me better explain why insulin is the bulwark of treatment in these patients compared to Type II Diabetes. Lastly, it helps them remember that Eli-Lilly makes a lot of insulin products because that's where they got their biggest start. Insulin has been around for less than a century, but diabetes has been around our entire species timeframe. For many students, this is taken for granted.

History serves as a launching point in a medical discussion for students on the seriousness of the topic by establishing how far we have come, and serves as a rationale, in my mind, for why our current practices are the way they are, and what may be future problems. The opioid epidemic aside, another issue we are currently facing is the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. When talking about infectious diseases, I like to discuss with students the seriousness of infections and what tumult society has gone through in the past.

Preventing Past Events

Is one of the main reasons for the progression of Medicine.

Many students have heard of the 'Black Death' and Bubonic Plague that Europe and Asia suffered during the Middle Ages, but many have not heard about the Spanish Flu (or the Influenza Pandemic of 1918) that killed over 50 million people worldwide in the early 1900's. In an age where influenza vaccination is taken seriously, it's hard to imagine a disease wiping off over 3% of the world's population in a span of a few years (more than those lost in the first world war). We have relatively few practitioners that remember treating measles, mumps, rubella, whooping cough, smallpox, etc. Vaccinations have helped move the curse of these diseases to the background of other diseases in most industrialized nations. And yet, we also rarely see people die from simple wounds and infections as well, as we have been benefiting from the widespread adoption of antibiotics since the invention of penicillin in the early 1900's. But now, with resistance patterns building up, we are turning back to older drugs that we haven't used, and are hoping for new ones to add to our toolkit. Helping students understand the widespread social impact of infections and their ramifications from a historical perspective I feel can lead to students understanding the importance of responsible antibiotic use and public health initiatives, even if the diseases aren't readily visible anymore.

I practice primarily in a heart failure (HF) clinic and focus on cardiology topics with my students. But, every rotation I start, I emphasize to students that everything I will teach them could be outdated within 5-10 years. We are making significant advancements in the treatment of HF, and what I learned in school is drastically different in a short amount of time. I remind students that the bulwark of drugs used in HF treatment was only invented in the previous three decades, with most landmark trials coming from the late 80's to the present. Why should students expect that when they go out into the medical environment things won't change more? Lifelong learning is an important item to impress upon students in medicine, that what they learn is likely to change substantially over time and they will have to adapt.

So I will leave it with this, if you are a student, ask yourself if you understand the history of treatment for the disease you are studying, it may help put things in better perspective. For educators, take the time to frame the history behind a topic you are teaching. One of my most favorite historical conversation was with a cardiologist in his 80's about his use of mercurial salts as diuretics before the advent of loop diuretics in the 50's. It's fascinating to see how far we have come and gives much thought to where we are going. Even if it's from your historical perspective, it can still be a valuable teaching anecdote.